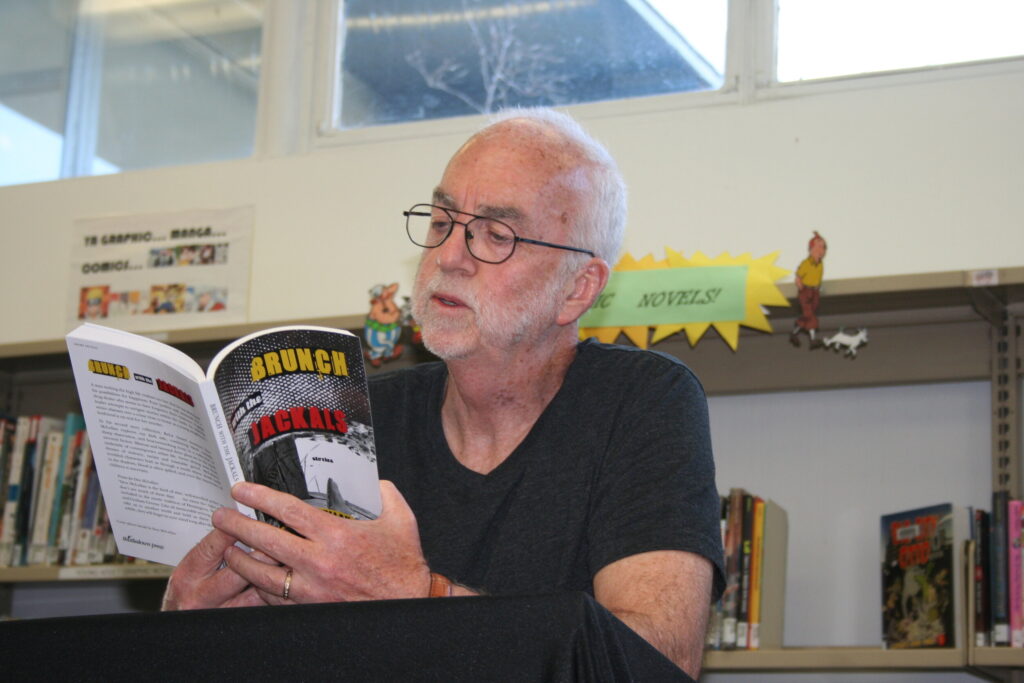

…with Don McLellan, who interviews himself about himself (because nobody else would).

DM-1: Many writers have artistic or academic parentage. And you?

DM-2: I grew up in a veterans’ housing project in East Vancouver. My dad had served in the navy during the Second World War and saw plenty of action, so we qualified for one of the six hundred sought-after bungalows. My mother, of Scottish/French ancestry, sold shoes at Woodward’s department store and developed film for Kodak. I always got the feeling the war satisfied in my dad an adolescent yearning for adventure, which I seem to have inherited. ‘I got fed regularly,’ he’d say when prodded. ‘I saw the world.’

After the war my dad worked in a non-union meat-packing plant and drove a taxi on weekends. He was active in a successful year-long strike for union representation at the plant, and was afterwards sponsored by the U.S.-based union to attend a labour college on Vancouver Island. In 1972 he was selected to present a contribution to George McGovern, the U.S. presidential nominee, at the Democratic Party convention in Miami Beach. (McGovern lost to Nixon.)

But there was more to it than that. I know he had a tough childhood. He and three younger siblings had been orphaned at an early age; they’d been passed back and forth between relatives in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and the West Coast. When concern for their survival waned, they were deposited in a Catholic orphanage. My dad never explicitly said so, but going off to a war seemed preferable to scratching out a living in Depression-era Canada. I know a grandmother also helped raise the homeless four. She was always spoken of with great reverence.

My mother didn’t finish high school – a lot of working people in those days didn’t – and my dad never started, so he struggled with the written word. I remember his anxiety when he had to sign my report cards: You’d think he was being tasked to perform open-heart surgery, or maybe his trembling hand was due to my pedestrian academic standing. He subscribed to the daily newspaper, though, scanning the headlines every night after dinner. His reading material of choice was the Racing Form, and his favourite place on the planet was the city’s Hastings Park Racetrack. If he could have rented a stall in the stables there and lived amongst his beloved ponies, I believe he might have left us.

On my annual vacation I took a boat to Pusan, South Korea. Many older Koreans could speak some Japanese – Korea had been a colony of Japan for many years – so I was able to get around on the Japanese I’d acquired. In the bus station in Seoul there was a mix-up with my ticket. A beautiful girl who spoke some English appeared out of the ether and straightened everything out. She was from Kang Neung, the beach town I was trying to reach. We’ve been married now for more than forty-five years. We have two daughters and two grandchildren.

DM-1: Did your background influence your writing?

DM-2: Many of my efforts feature working-class people in working-class settings because that’s who I know best. As a journalist I’ve met countless privileged folk, and would probably be classified today as modestly middle class, but I believe the stories of the comfortable are best penned by those on that side of things. Sharp readers can smell bullshit.

DM-1: Did any particular books influence your career choice?

DM-2: I remember enjoying a series of young adult novels about sandlot baseball players the school librarian recommended, and the Vancouver Public Library used to send a mobile library into the Project, a yellow bus, which I frequented faithfully. As a teenager, browsing in a used bookstore, I stumbled across Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which probably changed my life more than any other. The stories I remember best, though, were not written, but oral. Stories were the primary entertainment at our house when friends and relatives dropped by, and arguing politics was a blood sport. The instigator of many of these debates was an uncle who’d been too young for the war and thus able to matriculate high school, making him the family Einstein. We duelled verbally until his passing.

DM-1: What made you want to be a writer?

DM-2: I don’t have any inside dope on what compels one to write; I certainly wasn’t encouraged. In my early years there were good union jobs to be had in the mines, in the woods, on a fish boat, or in a lumber mill, so some people considered dropping out of school a calculated economic decision. Rich kids get an education, a lot of folks believed, and working class kids get trained, even the bright ones, as university tuition in those days was beyond the means of many. Several of my friends became longshoremen and, because of a strong union, made a lot more in their lifetimes than many university grads. By the time boomers came of age, progressive governments were opening up higher education to we commoners, and some of us took a run at junior college or university. Student loans, grants, and scholarships were made available.

That storied decade was a great time to grow up. Change was in the air, cages were being rattled, so there was much for a budding writer to draw on. My dad thought that I, a C+ student in a good year, should go to vocational school; a friend of his was a log grader, and he wanted me to be one. I told him I was thinking about university, and that I wanted to be a writer, though I didn’t really know what I was talking about. I remember him rolling his eyes the way a father today might when a son announces he’s gonna lay down some rap tracks with his homies. (Image the reaction if I’d aspired to be a ballet dancer!) But before one can be a writer, one must be a reader, and I was. To my parents – to many working-class parents, probably – sitting at a desk reading and writing isn’t real work. Some viewed it as a kind of advanced colouring. I always found this ironic considering the exertion required for my dad to reproduce his John Hancock on official documents. My brother got the message and became an electrician. Now that, my boy, is work.

DM-1: Had you ever met a writer?

DM-2: A pal from the East End moved to Abbotsford, in the Bible Belt east of Vancouver. His mother bought a coffee shop next door to the weekly newspaper, and his sister was dating the editor, this Englishman who’d coasted into town off the freeway one day, his car out of gas. The garage owner gave him a fill-up, but he had to leave his passport behind until he’d paid for the fuel, thus the job at the newspaper. He was a fascinating character, unlike anyone I’d ever met, an adventurer and raconteur. I don’t know if he ever wrote a book, but he was the first person I’d met who could have stepped out of one.

DM-1: When did you start working at the Vancouver Sun?

DM-2: The first time, when I was in high school. I was paid $21 for a six-day week jumping on and off a running board at the back of a moving panel truck delivering bundles to stores, newsstands, and hotels. One misstep and I would have been road kill. I had some magnificent falls on slippery floors and icy roads; that sort of thing wouldn’t be allowed these days. On the plus side, I got in great shape. A car knocked me to the ground once, some old duffer, but I was okay. Another time a German shepherd tore a chunk out of my leg. It was around this time that I started reading the newspaper regularly; I preferred it to the drudgery of homework. There was an older kid up the block, Phil, a heroin addict, who used to scrutinize the Province, the city’s morning paper, and pontificate to some of us about developments around the world. I enjoyed listening to his alleyway lectures. Something of a role model, was Phil.

I remember being in the Sun cafeteria before work one day when the columnist Allan Fotheringham, the editorial department all-star, was holding court. I recall concluding that being a famous writer was preferable to dodging cars for $21 a week. With the money I saved that year, me and a friend hitchhiked from Vancouver to New York City and back; it took us most of the summer. I repeated the exercise a couple of years later via Seattle, as well as a memorable three-month solo hike through Mexico starting from the Yucatan Peninsula. Plenty of young guys in the Sixties and Seventies were doing that sort of thing; it was part of the Zeitgeist. Taken together, these experiences were transformative. Years later, I wrote a short story, “Scram,” inspired by these low-budget tours. It was published in Descant, the literary journal, in 2003, and included in my first story collection.

DM-1: Talk about your education.

DM-2: I bummed around for a couple of years after high school wondering what to do with myself and working crap jobs. I took my first two years of university at Vancouver City College (now Langara College). There were a lot of people studying there who had worked and travelled – a different breed from the ambitious honour roll eighteen-year-olds who marched directly to university and went on to rule the world. (To see how that turned out, pick up a newspaper…if you can find one.) I credit several of my instructors at this lowly institution with instilling in me a lifelong love of learning. I’m puzzled by people who attend a so-called ‘good school’ and who, once credentialed, rarely pick up another book. People who can read but don’t have no advantage over those who can’t read at all.

Attending an expensive, name-brand university might get you in the door of a company or an entry-level position with some government, but being reliable, honest, and hard-working will keep you on the job when the boss is looking to ditch dead weight. The idea of a ‘good school’ is a scam perpetuated by everyone from the administrators on down to the students whose parents can afford the tuition. Of course there are some great profs at those schools, but there are also plenty of duds. Learning is not about the profs or the ivy draped over its venerable stone walls or the size of an institution’s endowment. It’s about the student. Eventually everyone has to swim out to the deep end and make it back on their own.

One of my fellow students at City College was John Orysik, who had written a jazz column as a teenager. He went on to become the co-founder and media director of the Vancouver International Jazz Festival. Another fascinating character was Ian Caddell, a loquacious, larger-than-life sort who had encyclopedic knowledge of American electoral politics. He and I used to cut classes and debate away the afternoon in the college cafeteria. When we transferred to Simon Fraser University, Ian became editor of The Peak, the campus rag, and he encouraged me to contribute. My first published piece was a Q&A interview with the up-and-coming playwright Tom Cone. Once I got a feel for journalism, I was spending more time writing for the paper than studying. While I was still in school, I also sold a couple of pieces to the Georgia Straight, the once-alternative weekly, and to the Vancouver Sun. Ian went on to a long career as a movie reviewer with the Straight and as editor of Reel West, a trade magazine for the movie biz. He passed away a few years ago; the film industry named an award after him. There were many others: Rasunah Marsden became a fine poet and editor of First Nations literature; Gary Salloum went on to become the lead lawyer for an international energy corporation. Not graduating from Harvard didn’t stop them.

DM-1: Did you graduate?

DM-2: Yes, and with one mother of a debt. There was about as much demand for an English degree then as there is now. I studied Canadian literature with George Bowering, who has authored about a hundred books and served as Canada’s first parliamentary poet laureate. The most enjoyable course was a directed reading class with the English prof Dan Callahan. He drew up a list of ten contemporary novels from around the world. We’d meet in the pub once a week and talked about the readings, and I’ve been hooked on international fiction ever since. I also think I was impregnated that summer with the notion that I might one day write fiction. I was penniless when I finished school, but hey, it was the Sixties, and poverty was cool, man. I didn’t have to pretend.

DM-1: Did you go to grad school?

DM-2: Are you kidding? I got a job making bread, and not the kind you spend. It was a factory operation mass-producing white loaves and hamburger buns. I was on call, the night shift, and the heat, when you were manning the ovens, could make you dizzy. I hated the job, it was Dante’s Inferno, but it was good money, union money, and it was nice to hear some coin rattling around in my pocket. But I was inhaling flour all night long, so I was coughing up gobs of the stuff. If I had stayed working there I think I would have blown my brains out.

DM-1: How did you catch on with the Sun?

DM-2: The paper’s features editor, Mike McRanor, whose minimalist columns I had always admired, liked one of my freelance pieces and offered me a job. He called me up out of the blue; I thought I was being pranked. The journalists I worked alongside – people like Don Stanley, Scott Macrae, Max Wyman and Lloyd Dykk – were very supportive. In the beginning I just tried imitating them. I asked a lot of questions and mostly kept my trap shut. I wrote features, profiles, reviews, a little news, offbeat stuff. I filled in for whoever was out of action or out of town. I only worked at the Sun for a couple of years, but if ever I had a lucky break, that was it. Having worked for a big city daily led to subsequent opportunities in print media.

We all have people who have greased the skids for us. Mike McRanor’s name is at the top of my list. He lived nearby, and we’d meet up for coffee and exchange emails. He was largely self-educated, the last of a breed, and a voracious reader. I always looked up to him, he was a kind of father-figure to me and many others. The cancer took Mike in 2023. I still miss him.

Journalism was heady stuff for a boy from a public housing project. Like everything else, if you like it, if you try, you’ve got a shot at becoming reasonably good at it. As a journalist you talk daily to people of every stripe and persuasion – rich, poor, good and bad. Fertile ground for a wannabe fiction writer. It sure beat working for a living.

DM-1: Did you ever meet Fotheringham?

DM-2: He’d sometimes toss me a ‘how-ya-doin’-kid’ when he passed my desk, but I doubt he ever knew my name. He was quite the dandy, the Foth. He wore these Don Cherry-like shirt collars and silk ties, and he always had this cool smirk on his face and a bit of a swagger. (The conservative apparatchik Dalton Camp said of Fotheringham that “he’s the only standup comedian who works sitting down.”)

I once wrote a cheeky review of a Tina Turner appearance at a local club. This was prior to her comeback, and the show was more striptease than concert. I had too much to drink that night, and my review, if memory serves, expressed an appreciation of her shapely black thighs. I remember being concerned how the story would be received – wondering if it would be published. I found a note in my typewriter the next day. ‘Nice piece,’ it said, ‘Foth.’ I’m not one to collect mementoes, but I’ve kept a copy of our wordy exchange.

Several of us young writers at the time were under the spell of New Journalism, which encouraged inserting oneself into stories and using fictional techniques to enliven a narrative. This was the mid-Seventies; the decline of print and long-form journalism was just beginning. One day we were told our articles had to be shorter so that photos could be larger, an unsettling portent for a written product. The tone of our pieces was to be in the key of ‘light and breezy,’ as though superficiality would somehow save the industry. Little did we know at the time that digital loomed, which has been good for the trees, but not so good for we scribblers.

DM-1: What was next?

DM-2: I’d always fancied the idea of writing fiction – I never stopped reading it – and I made many an attempt over the years, but every effort ended in failure, affectation or abandonment. In retrospect, I think I lacked patience and discipline, so for a spell I just threw up my hands and walked away from the typewriter.

I’d heard there were jobs with English-language papers overseas, and I knew there were English teaching jobs. I still owed a shitload of money for my student loans – I had borrowed the maximum allowable limit – but I was feeling restless, so I signed a two-year contract to teach English in Osaka, Japan. I had this fanciful notion to work my way around the world, paying off my loan along the way. The school underwrote the plane ticket and set me up in a tatami-mat apartment in Ishibashi; over there, my useless English degree had some value. I taught conversational English to bankers, blue collar workers and engineers at massive industrial centres owned by the zaibatsu, the country’s conglomerates. Most of my classes were in the evening, after my students had finished their shifts. I had a ball over there, I was drunk almost every night, but living and working in Japan was not easy. They are a remarkable people, the Japanese, a special people, and I’ll never forget their kindness, but the customs are quite rigid and conservative, and nonconformity is not tolerated – not a good fit for a Goodtime Charlie.

When my two-year contract in Japan ended, my student debt finally retired, I found work as a sub editor at the Hong Kong Standard, the second largest of five English-language dailies in the British colony. Besides local Chinese, my colleagues on the Standard hailed from the U.S., the U.K., Australia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, South Africa, Burma and Macau. It was a fabulous experience, an annus mirabilis. After a year my wife became pregnant with our first child, so we returned to South Korea, where I found work as a copy editor at the English-language, government-controlled Korea Herald.

Few western journalists were keen to work there, as the country was run by the dictator Chun Doo Hwan, and there was always talk of war with the north, a short cab ride up the highway from our apartment. Before the paper could go to the printer. a censor scanned the pages for treason. Chun’s photo was on the front page every day; it was mandatory. His wife’s photo was on the back page. It was the first time I’d experienced the collective fear of a people, of a state terrorizing its own citizens and spoon-feeding the population what its generals wanted them to read. People would lower their voices and look over their shoulders when discussing anything political, as informants were everywhere. There was also a nightly curfew, and you had to spend the night in a bar or club if you lost track of time. Protests were quite frequent downtown, and several times when I was leaving work the streets were filled with military patrols and the air thick with tear gas. Of course there was never a mention of unrest in the Herald. As a sheltered Canadian, I had to pinch myself: this wasn’t happening in a movie.

In 1996, Chun – The Butcher, dissidents called him – was jailed and sentenced to death – and later controversially pardoned – for his role in the Gwangju Massacre. His bloody reign has since become the subject of books and movies. I fictionalized my experiences there in the short story “Massacre of the Innocents.” It was longlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2018.

We returned to Canada in 1982; I’d been away for almost five years and experienced a bout of culture shock. The country was in the grips of a nasty recession, and I couldn’t buy a job. After a painful dose of unemployment I landed a job writing for a weekly travel trade publication, staying a few years. I later edited a magazine for seniors and freelanced widely. I set up a home-based corporate communications operation anchored by newsletters for an oil refinery and one of the province’s largest law firms. I also started my own publication, the Killarney Times, a community news and information quarterly. I did all the writing, and designed and sold the ads; my wife and the girls helped deliver it. I never made a nickel with the Times, but I had a great time while it lasted.

My last paid gig, managing and editing an insurance industry publication, lasted a dozen years. Working for trade mags and smaller outfits – the mid-minor leagues of print journalism – turned out to be something of a blessing. As the big city rags were hollowing out, laying people off, I was able to survive a while longer.

DM-1: When did you start writing fiction?

DM-2: Thirty-odd years ago. My kids were less dependent by then, so I had more free time. I also gave up cigarettes and alcohol, and for almost three decades now I’ve been so clean I squeak. (“Write drunk,” it’s been said, “but edit sober.”) It took some years for me to realize the effect this would have on my attempts to write fiction, and on my life in general, but I can say now that sobriety was one of the wisest moves I’ve made. Sober, I started running. It cleared my head and allowed me to commit. Maybe getting older had something to do with it, too. I know a lot of writers believe intoxicants stimulate the imagination, it’s part of the literary mythology, but it constipated mine. I wrote my stories before and after work, and on weekends. For the first few years just about everything I submitted to lit journals was rejected. Though there isn’t any real money in writing literary fiction, its athletically competitive, publishers are swamped with submissions. Some journals publish only one or two per cent of them, and the number of book publishers underwriting story collections grows shorter every year. In my case, the old adage that a writer could wallpaper a room with rejection slips is no exaggeration. I considered packing it in many times, but for some reason I didn’t – I couldn’t. I’m sure some friends and family members think I’m nuts, and maybe being nuts is what it takes to write literary fiction in a Facebook world. I advise the small number of individuals who seek my advice about literary fiction never to assume riches await or more than a few people will buy your books. Do that, and you’ll not be disappointed, and if you’re not disappointed, you’re probably a writer.

A reviewer once referred to much contemporary literature these days as ‘pretty sentences all dressed up with nowhere to go.’ Andy Warhol might well have been thinking of such experimental writing when he defined art as ‘whatever you can get away with.’ Raymond Carver wrote stories to address his concern that life is short and ‘the water is rising.’ Alice Munro said she’d rarely read a novel that wouldn’t have made a better short story. Journalism must inform accurately, and under unwavering deadlines, but it need not entertain. In fiction, Alistair MacLeod admonishes, ‘if the writer doesn’t staple the reader to the page, they will put down your book, go to the kitchen and make a cheese sandwich. And they won’t come back.’

DM-1: Why do you prefer the short story over the novel?

DM-2: It’s often said the novel is like a marathon, the short story like the hundred-yard dash. But the differences are many. There’s a tremendous challenge telling a tightly crafted tale. The reader is parachuted into a character’s life for a day, a few hours, a moment. The writer’s tools are nuance, subtlety, clues and, of course, brevity. The economic history of a character can be conveyed in a single line of dialogue, which the Irish writer William Trevor was getting at when he referred to the short story as ‘the art of the glimpse.’ (His compatriot, Claire Keegan, maintains that every story “has its own scent.”) Someone else has said stories are a way to dignify experiences. With the short story the writer can showcase different forms, styles and voices. Novelists labour for years over a single yarn, and they can have a difficult time getting publishers to read it. Of course there are many brilliant novels being written, and I’d give it a try if the right idea came to mind, but far too many of them feature copious padding, as today’s book market demands heft, and heft means the sacrifice of more trees. The trade-off isn’t always worth it.

DM-1: Why should we put down a good spy thriller or police procedural and pick up a collection of dense or difficult literary fiction written by an author no one has ever heard of?

DM-2: You might add: And no one ever will. Most genre fiction is predictable. It’s formula, it’s write-by-numbers. While these books have more readers than mine, millions probably, I like to think my stories – at least the stories I aspire to write – get more of the reader. Dylan Thomas said that when a new poem arrives, the world is never the same. I believe this can also be true of a good short story, and that’s why I’m still trying to write one.

In 1999 the now-defunct literary journal Pottersfield Portfolio of Sydney, N.S. accepted my story “Fugitive.” It was my first published fiction. I was 48 years old.

DM-1: Talk about journalism and short stories.

DM-2: Most journalism and non-fiction is about the outside world. Literary fiction is about the inside; it goes where journalism and non-fiction can’t, or so many of its adherents proclaim. The brilliant writer Carys Davies, also a former journalist, said it best: “Non-fiction has scaffolding. Fiction has none.”

I’ll put my bias up front: In some ‘short fiction,’ a nebulous category, along with parlour game offshoots such as micro fiction and flash fiction, anything goes. In place of a discernible narrative, there is cleverness and word play and self-absorption, but too much of it is an exercise in simple nothingness. It’s creative writing, of course, and some of it’s genius, but not necessarily a story. Some say Ernest Hemingway is the author of what is probably the most widely circulated six-word story, apparently scribbled on a napkin – ‘For Sale: baby shoes, never worn.’